An Ashes series is taking place in Australia and things are going badly for the old country. The selectors have picked the wrong team twice in two attempts, chances are being muffed and one of English cricket's narrow-eyed folk villains is settling some not-so-old scores. All this against the background of a pandemic. There's not been a series like it. "Maybe not exactly like this," one imagines David Frith saying, "but you might remember that Test when…"

Perhaps that's the point. You

might remember; Frith almost certainly

will. Ashes cricket has been one of his passions since, aged 11, his reverie on Rayners Lane railway bridge in 1948 was interrupted by the news that Australia had

skittled England for 52 at The Oval. That experience is recalled in characteristically needle-sharp detail in chapter three of

Paddington Boy, Frith's updated and considerably revised autobiography. His first attempt,

Caught England, Bowled Australia, was published in 1997 and its title reflects the intriguingly blended identity of a Londoner who spent his childhood in England and adolescence in Australia, only to return home in April 1964 accompanied by a wife and three children and nurturing the daft idea that he might make it as a cricket writer.

Frith succeeded to the extent that he is now regarded as one of the game's finest historians.

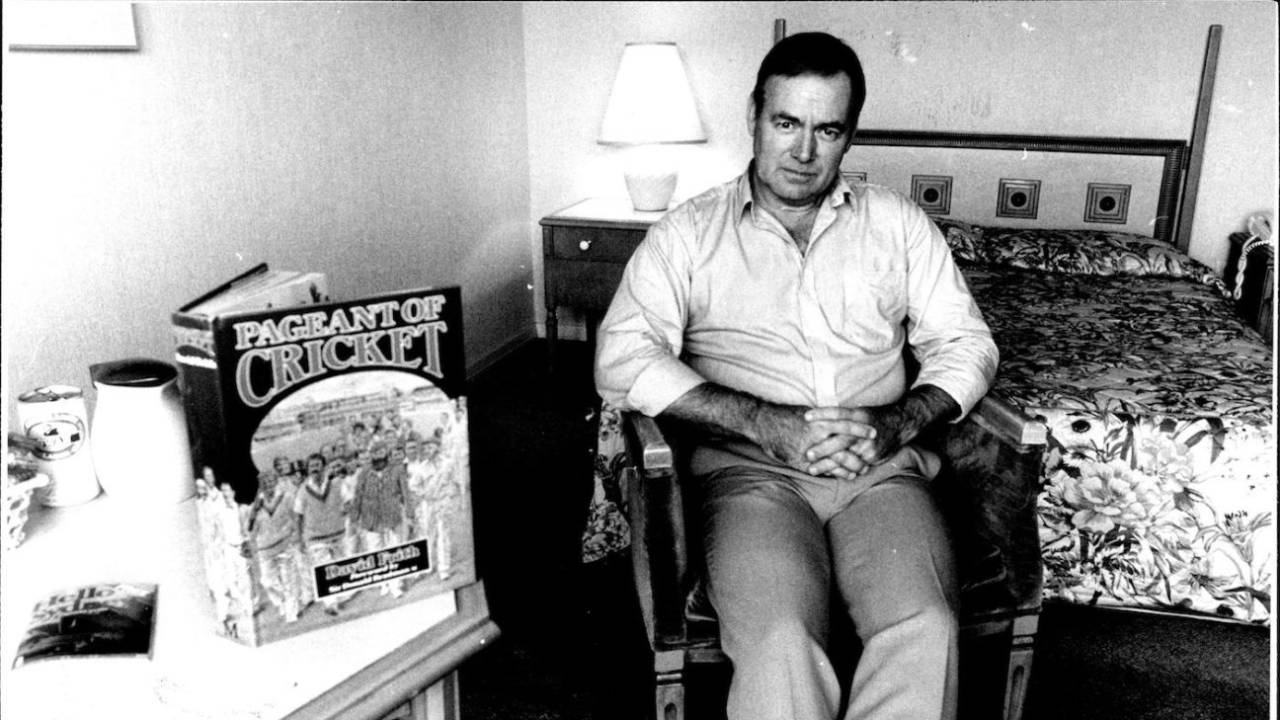

Pageant of Cricket, his pictorial history of the game, has no equal; his book

Bodyline Autopsy is the best in an absurdly crowded field; his biographies of AE Stoddart, Archie Jackson and Ross Gregory mix sympathetic insight with tough analysis and are the products of proper research; his original book on cricketers' suicides in 1990 turned fresh turf decades before counselling was a thing.

We could go on, and maybe we should. For, bizarrely, Frith has not been sufficiently honoured in either of the countries he called home. One could name about 20 young cricket writers, most of them with a decent knowledge of the game and some awareness of its history, who would benefit from an afternoon with him at his house-cum-library in Guildford. That shrine to one man's devotion to the game is decorated with such glorious pieces of memorabilia as Bert Oldfield's blazer from the 1930 Ashes tour and a ball from that year's Trent Bridge Test, both of which were given to the near-obsessed youth in the 1950s, a decade in which he also frequented the sports shops owned by Stan McCabe and Alan Kippax.

Frith's autobiography contains accounts of those meetings and also of his later conversations with players like Wilfred Rhodes, Sydney Barnes and Percy Fender. By then, Frith had established himself in the cricket world and was determined to waste no opportunity to interview old players while he still could. To a degree, his journalistic reputation was made by his coup in getting an interview out of Jack Gregory, who never talked to reporters until Frith drove 200 miles in the hope he might chat to this one.

While all this is lovingly recounted in Paddington Boy, the book would be a lesser thing if it was simply a chronicle of personal achievement. One of the reasons why Frith's work will live on for as long as cricket is valued is that he sees beyond the statistics and the accomplishments that satisfy others in his trade. He knows he will never write properly about the cricketer if he doesn't understand the person, and that principle is also exemplified in the many passages of self-analysis where Frith reflects on the influences and events that formed his own character.

For example, here he is on the afternoon when his ambition to be a cricket writer was probably conceived. It is January 8, 1951 and he is paying his first visit to the Sydney Cricket Ground to watch the third day of the

third Test against England:

"I looked around me in wonderment, at the enchanting green 19th-century pavilion with its ornate roof and clock-tower, at the roomy and elegant Ladies' Stand, and the long, cosy Brewongle Stand… The Hill was packed. Beer-cans were a future invention still. Hundreds of men sat on that great grassy expanse, almost all of them wearing wide-brimmed hats, some of them yelling encouragement to the Australians, not that they were in need of it, some directing ribaldry and gentle derision at the Englishmen. It was a momentous baptism, a revelation, destiny-making."

Two years later and the 16-year-old Frith is at home: "The diary records my listening to the Hassett testimonial match on radio, bowling alone against the school wall, noting the deaths of Warren Bardsley and Fred Root, and being concerned at England's performance in the first Test in the Caribbean."

Paddington Boy is packed with such evocative passages but it is much more than a cricket writer's autobiography. It is a rich account of what it was like to be a boy during a war in London and then grow to manhood in 1950s Australia. It is the story of how a young bloke eventually built a career for himself and a life for his family in England and developed into one of cricket's most indefatigable researchers. And it is also a moving love story about Frith's long marriage to Debbie, who passed away less than three years ago. The final chapter contains Frith's honest attempt to cope with the loss of someone whose presence could light a room.

There are other tough chapters in the book; Frith's life has not been a ride up sunshine mountain. Having been appointed editor of the Cricketer, he was removed from that post in 1978. The following year he founded and edited Wisden Cricket Monthly, a vibrant competitor to its increasingly staid competitor, and was then replaced as its editor in 1995. This latter blow hurt him deeply and it still does. Disingenuous conciliation is not his style and readers of Paddington Boy should be grateful. This is a very honest book and its author does not spare himself. He is still bitter because he still cares.

And so you can bet that dark mornings in Guildford will find one octogenarian following yet another Ashes series, even if its outcome appears as inevitable as that of his first, in 1948. But if you read this deeply scrupulous and rather wonderful autobiography - and you certainly should - you will find that the boy who leant on a railway bridge over 73 years ago is still alive in the book's eminent author. For some reason, I imagine Bert Oldfield would be quietly pleased by that, and I'm certain Debbie was already very proud.

Paddington Boy

By David Frith

CricketMASH

448 pages, £17.95

Paul Edwards is a freelance cricket writer. He has written for the Times, ESPNcricinfo, Wisden, Southport Visiter and other publications